In this article, you will learn:

- Why monitoring cash flow ratios is important.

- How to analyze different cash flow ratios to provide significant insight for your church.

- Recommended benchmarks for cash flow reserves and measures.

- How to use cash flow ratios with other ratios to gain insight into what is driving certain trends.

Introduction

In many regions of the U.S., seeing treetops start to turn bright red and yellow is an indication that the weather will soon get colder and winter will come. Then we look for the first frost, the first snow—and ultimately the first sign of spring, when that lone piece of green breaks through the melting snow.

Watching the landscape for seasonal changes is not that different from looking at key financial indicators for your church. If you pay attention and study the signs, you can prepare for what lies ahead.

This article is the second in a series on how effective financial ratios can give your church vital insight into its financial condition and trends. We previously looked at how to get the most out of your financial ratio analysis. Now we’ll discuss how to analyze cash flow ratios, using sample ratios from the CapinCrouse Church Financial Health Index™ (Index).

Why Monitor Cash Flow Ratios?

You must have sufficient cash balances to run your church’s operations. Positive net income and net asset balances won’t make up for inadequate cash reserves to fund outflows. They also won’t help handle months when giving is down. A church without necessary reserves will be scrambling to operate in the short term, no matter what the other balances are.

It is important to consider debt and other ratios alongside your cash flow ratios. It’s also prudent to consider upcoming capital needs that have not been accrued or paid for and the impact they would have on these ratios. For example, if your church needed a new roof at a cost of $500,000, you would need to consider this when looking at cash flow ratios and the impact pending expenditures will have on them. It’s the same decision process a church uses when deciding to maintain cash reserves versus spending them to pay down debt or pay for construction instead of financing it with more debt. It’s all interrelated.

Days Ratios

These ratios are designed to tell your church how many days of cash reserves are on hand by looking at cash from three unique perspectives. We discuss these ratios in further detail below.

Days of Operating Cash and Investments

Operating cash and investments are those resources that do not carry donor restrictions on the assets and are available for the church to spend without restrictions. This ratio calculates the days of operating cash and investments that are available to fund annual expenditures, but specifically related to very liquid assets. It only considers operating cash and investments, not other current assets and liabilities. Operating investments would exclude funds for endowment, split-interest agreements, and other non-operating purposes.

This total is divided by total cash expenses the church would incur. This amount is calculated by taking expenses, excluding the largest non-cash expense of depreciation, and adding current debt principal. Current debt principal is added back because it represents cash spent but not recorded as an expense in the statement of activities.

How to Analyze these Ratios

Let’s look at some sample ratios that have very different results and trends, and what this may indicate for each hypothetical church.

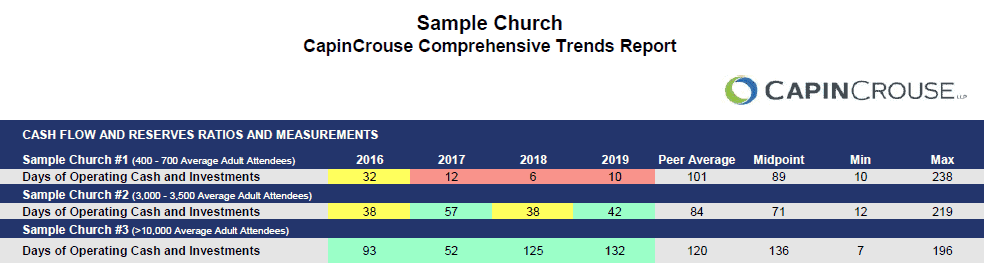

In 2016, Sample Church #1 was just outside of the recommended benchmark of 40-80 days of operating cash and investments. You can also see it is far below the average and midpoint of their peers.

In addition to the individual results of the church versus peers and the recommended benchmark, you can also look at the trend of the ratio between years. Sample Church #1’s trend is cause for concern because it shows that after 2016, their result dropped significantly and remained low. This indicates that the decrease wasn’t caused by a one-time expenditure or event—it’s the result of some other underlying cause. This could be a decrease in contributions or a significant increase in expenses to the point where the church can’t fund current operations from annual contributions. Most likely, it’s a combination of both. Looking at the Debt, Contribution, and Expense ratios will help this church see what is driving this trend.

Sample Church #2’s results fall just within or just outside the recommended benchmark. However, the trend shows their reserves lower in one year and increased to a result within the benchmark the next year. One reason could be that the church is funding other initiatives that cause them to spend their reserves but rebuild them in alternate years. Seeing that reserves come back within the benchmark and that they are not too far off from the midpoint of the range appears to support this.

You can also look to the other ratios to indicate why these results are going back and forth. Is it because they’re spending and rebuilding reserves, or are attendance and contributions fluctuating? Although you can’t discern this from the cash flow ratio alone, it’s important to understand what’s causing the change between years. Looking at just one indicator instead of the combined ratios in other areas is similar to the difference between looking at a two-dimensional picture compared to a three-dimensional hologram. You get more information from the additional dimension of the hologram. The same is true when you look at several ratios and measures in conjunction with each other.

Sample Church #3 is above the recommended benchmark and has increased their reserves every year except 2017. Even the 2017 result was within the benchmark. As you can also see, the peer average is extremely high. Churches in this attendee range appear to be running at this higher level of reserves (above the benchmark), so results above the benchmark are not unusual or unexpected.

Analyzing the trends, benchmark, and peer information of these ratios provides significant insight. And while it doesn’t answer every question you may have, it does tell you where to look next.

Available Days of Cash Flow Coverage

This ratio is the sum of:

- How much your church has on hand at the beginning of the year that is available to spend without restrictions (operating cash and investments), plus

- The cash you will generate during the year from day-to-day operations (cash flow from operations from the statement of cash flows), plus

- Additional cash that could easily be borrowed, if needed (available operating line of credit).

This total is divided by the sum of cash expenses plus mandatory debt service payments. The result is multiplied by 365 to convert the ratio into days. The final product shows how long your church could continue to operate on these sources. It’s the maximum level of reserves and should always be the highest of the days ratios that calculate cash reserves in the Index.

Since this ratio includes cash flow from operations, it is typically the biggest influencer of the result. If a church has extremely high positive cash flows from operations, that will increase the ratio. The same is true if the church has significant negative cash flows from operations. The numerator also includes prior-year operating cash and investments, which if high (or low) may also increase or decrease the ratio. Finally, this ratio also includes the impact of an unused operating line of credit. If your church does not have this, it may not be comparable to other churches that do and are able to add it to the calculation.

Think of it as how much you have on hand at the beginning of the year plus what you are going to generate during the current year and what you could borrow for operations. Let’s look at our examples again:

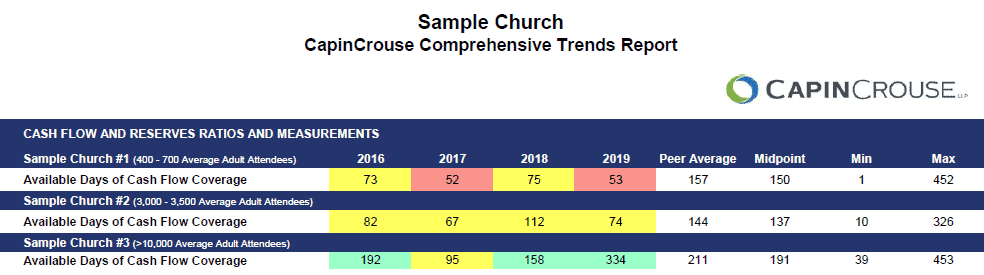

Sample Church #1 has mixed results but is trending down and is significantly below peers. Some years they are outside of the recommended benchmark of 120-180 days of cash expenditures on hand, which puts them in the warning range. In intermittent years they have less than 60 days of reserves on hand, which is the low end of the benchmark and in the red flag range and requires immediate attention. Most concerning, Sample Church #1 is struggling to bring their reserves back up consistently. Comparison to the result of the Days of Operating Cash and Investments on Hand ratio further proves that they are having issues maintaining adequate reserves. It’s likely that the church has negative cash flows from operations in the years the result is below 60 days, which means they are losing cash in their day-to-day operations. If this trend continues over the long-term, the ministry of the church could be permanently threatened.

Sample Church #2 is outside the benchmark and below peers, but always above the minimum of at least 60 days of reserves on hand. When you compare this result to the Days of Operating Cash and Investments on Hand ratio, you can see that the church is able to pull this result up into the benchmark range. And although they are below peers, it could be that the level of reserves is supporting certain deliberate investments in new programs or infrastructure.

The key is to know if Sample Church #2 is intentionally making operating decisions that are keeping reserves at these levels or if they are unaware of what is causing this trend. A church that makes intentional operational decisions that could result in growth is less worrisome than one that has no idea what is driving the trend of their reserves. Talking to management and reviewing other ratios can complete the picture.

Sample Church #3 has a very healthy trend: Not only are their results improving, but they also are above their peers and more than double the low end of the recommended benchmark (120-180 days) in 2019. This indicates that the church has healthy giving and manages operating expenses well. They also probably don’t have a large amount of debt. The question for this church is how they are going to invest these abundant resources for the future to support growth in their ministry.

See how different the questions are between the three churches? All are supported by ratio results.

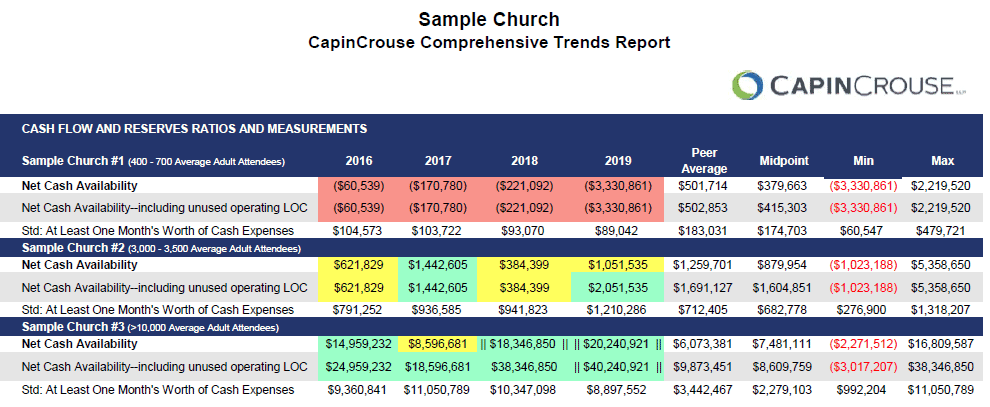

Net Cash Availability

This measurement calculates the amount of cash available for other uses after the church has satisfied its current liabilities and set aside appropriate funds for projects with donor restrictions that have not been completed. It is one of the most important measures provided to your church leadership because it answers the question “Whose cash is it and how much of it can we spend?” not “How much cash do we have?” These are typically two very different questions.

Sample Church #1’s results are negative, which is below the benchmark of one month’s worth of cash expenditures. The trend is also concerning because they are spending more and more money they don’t have, and the result appears to be growing exponentially. So how are they able to go so far negative? It’s likely that because other resources aren’t available, the church spent resources with donor restrictions to fund operations. While these resources are not a legal liability or obligation of the church they are not to be expended for general operating purposes, which is why they are excluded from the sub-total of net cash available that can be spent. A negative result indicates the church has likely spent resources with donor restrictions. Because of this, there can be an obligation to the donor if a church misspends its net assets with donor restrictions.

A negative result can also indicate that a church may be funding operations on short-term revolving debt. You can tell that Sample Church #1 isn’t doing that because their Net Cash Availability number is the same with and without the operating line of credit (LOC), indicating that they do not have an operating LOC. But it’s clear they have “borrowed” from resources with donor restrictions and don’t appear to be able to pay them back.

Sample Church #2 has wavered above and below one month’s worth of cash expenditures. Unlike Sample Church #1, however, they appear to have a plan to handle the fact that they are consistently going below the minimum benchmark. The measure shows that in 2019, the church took out a $1 million operating LOC. So while their net cash availability is below one month’s worth of expenses, with the availability of their newly obtained operating LOC they are within the benchmark. This is only a safety net, and with active monitoring of reserves and cash flow forecasting, they appear to be managing their operations.

Sample Church #3 is well ahead of peers, above the benchmark, and has consistently increased cash available to spend on operations. You can tell Sample Church #3 manages their cash reserves and is forecasting cash needs because the ratio shows that in 2016 to 2017 they had a $10 million operating LOC, and in 2018 they increased it to $20 million to handle shortfalls. While they don’t appear to need it, they are covering themselves with a two-month expense reserve through revolving debt.

You can also see that Sample Church #3’s average monthly expenses have decreased between 2018 and 2019. Since the largest two expenditures in most churches are personnel and debt, it’s likely that they have either pared down staff so they are running lean or paid down debt and have less interest expense. It’s probably a combination of these factors. To know for sure, you would need to analyze their debt and personnel expense ratios along with trends in attendees.

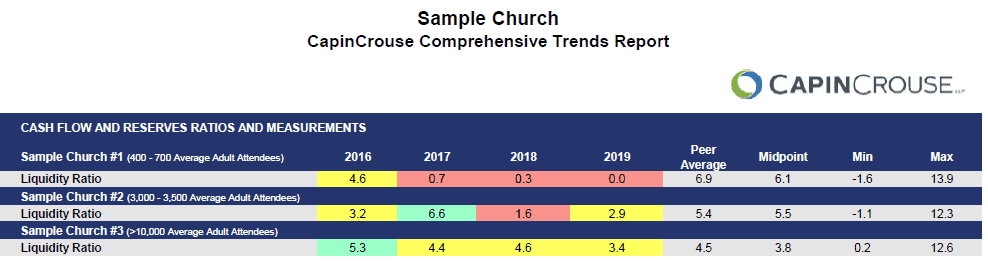

Liquidity Ratio

This ratio measures how operating cash and investments are able to cover current operating liabilities. The calculation is similar to the Current Ratio, except that it is only calculated on a portion of current assets (operating cash and investments). This is not the same as all cash and investments because it excludes cash and investments that support donor restrictions. And similar to the current ratio, this modified asset amount is divided by modified liabilities. Operating liabilities (those due in less than 10 days) exclude current building fund liabilities, which normally have a separate source of cash from revenues with donor restrictions. They also exclude any amounts owed on a short-term construction line of credit as these are typically interest-only until converted into long-term debt and paid over time. As a result, a short-term construction line of credit does not require payment from current operating cash or investments.

This ratio will tell the reader how many times operating liabilities can be funded from operating reserves. We believe a reasonable benchmark for this measure is greater than or equal to 5.0.

In Sample Church #1’s results, the main factor that stands out is the trend. While they are below the recommended benchmark and peer average, the biggest concern is that their result has decreased every year until they have a 0 in 2019. This indicates that not only are they unable to handle unexpected operating expenses, events, and new ministry opportunities that may come along, they also are not also able to handle current expenses necessary to operate on a day-to-day basis.

Sample Church #1 appears to have used all of their reserves and needs to drastically cut expenses to an absolute minimum to survive on current income. The most likely place to make cuts is at staffing levels, which are typically a church’s largest expense. While reducing staff may help Sample Church #1 survive in the short term, it won’t help them over the long term and will severely impact their ability to provide programs and services on an ongoing basis. It’s a tough place for a church to be and they are likely looking at closing their doors or combining with another church.

Sample Church #2 is below peers and the benchmark, and has fluctuating results between years. However, is the fact that they are not consistently trending down into the red flag range is a positive sign. They must carefully manage their operating reserves and make sure they increase at a rate greater than operating liabilities to improve this ratio. That will require careful cash forecasting and management, which their other cash flow ratios and measures indicate they are doing. It’s important for this church to keep a close eye on trends in these ratios in the future.

Sample Church #3’s results are trending down and below the recommended benchmark and peer average. However, their 2019 result is not far off from the midpoint of the range. The fact that the midpoint is further from the average shows that the results that make up the average are spread out, so the average is less important. It’s also key that their other cash flow ratios and measures are very strong. So this likely decreased between years due to an increase in operating liabilities. The church may have chosen to use resources in other ways (such as to pay off debt, which is a non-operating liability) and used their operating cash and investments to do so. In that scenario, operating liabilities could have increased because non-operating liabilities decreased.

Remember, the way to improve this ratio is to have operating cash and investments increase at a rate greater than operating liabilities. Knowing the reason for the increase in operating liabilities and what activity is happening in non-operating liabilities will answer the question. But looking at the other cash flow ratios and measures doesn’t indicate a reason for concern at Sample Church #3.

Just like noticing the leaves changing in the fall, if you know what to expect and can read the signs, putting these analytics together can provide a comprehensive examination of your church’s cash reserves. And that can be very valuable to your church leadership.

If you want to benchmark your church but are unsure where to start, ask about the CapinCrouse Church Financial Health Index. This convenient online tool is designed to help churches measure and analyze their financial strengths, weaknesses, and trends to see where they have been and map the best route forward.