The “Fire Drill” article below has a companion piece, entitled Sexual Abuse Response Planning. After reading this article, refer to the planning form; it’s a valuable framework for discussion/planning a responsive effort to an allegation—even a false one.

In classrooms across the country, school administrators lead faculty and students through mock disasters (fires, shootings, bomb threats, tornados, etc.) to ensure the existence of sound safety plans, communicate expectations to all involved, and determine any necessary changes or improvements.

A failure to drill potential disasters can lead to catastrophic results, generally with little or no warning. In the midst of a crisis, it’s too late to prepare; the catastrophic event simply reveals whether the organization took reasonable steps to prepare for a foreseeable event.

A sexual abuse allegation can cause significant difficulty, and organizations serving children should “drill” to better address these issues:

- Is a sound sexual abuse safety system in place?

- Do all staff and volunteers understand their role?

- Are changes or improvements needed?

Failure to prepare for this risk can lead to catastrophic results. Are your staff and volunteers prepared? How would your safety system “respond”?

A Sexual Abuse Fire Drill is essential

Assume an allegation related to a staff member, volunteer or participant is received by your organization. For purposes of this exercise, assume the allegation involves multiple victims and the accused is a trusted staff member or volunteer. With these “facts” in mind, walk your organization through all existing responsive steps, including:

- Insurance coverage issues and required notices and responses

- Statutory Reporting Requirement actions and responses

- Organizational Safety System elements and required responses

Insurance Matters

As to existing insurance coverage, the drill is designed to answer these questions:

- Does the organization have the correct coverages for a multi-victim claim?

- Does the organization have sufficient coverage (limits) for a multi-victim claim?

- Are there endorsements, riders, limitations or qualifications related to coverage?

Most child-serving organizations purchase insurance coverage through an insurance agent. During the insurance purchase or renewal process, the primary coverage issue negotiated relates to Property & Casualty (P&C). The P&C portion of the premium will typically account for the majority of the total insurance premium. Without an explicit Sexual Misconduct endorsement, sexual abuse claims typically fall within General Liability policy coverage—most general liability coverage will now include a separate sexual misconduct section. Few policyholders are familiar with the terms of the General Liability policy, the limits related to any sexual abuse claim, or terms requiring notice to the carrier when the organization “receives facts that could give rise to a claim.”

Recently, our law firm (Love & Norris) was retained by an organization facing sexual abuse allegations related to a trusted staff member, with four female victims, aged seven to nine. When asked, organizational leadership indicated that the organization had insurance providing $1 million/$3 million in coverage. When asked whether their insurance carrier was notified when the initial “facts” came to light, leaders replied “no.”

At this point, it was too late to “drill.”

Two significant shortcomings were revealed.

Insurance Coverage

First, the organization could not recall the name of their insurance agent. As a result, the organization could not quickly and easily understand what coverage was in place: Commercial General Liability Policy (CGL), Errors & Omissions Policy (E&O), Directors & Officers Policy (D&O) and/or Umbrella Policy. The delay was critical due to the fact that the crisis unfolded on a Saturday.

Second, the underlying policy did not provide $1 million/$3 million in coverage. Upon closer inspection, the policy included a specific “Sexual Misconduct” provision which limited coverage to $100K/$300K for sexual abuse claims. There was no E&O, D&O or Umbrella Policy.

Third, leaders indicated they were informed about the allegations early on, but failed to notify criminal authorities or their insurance carrier because the reports were “hearsay.”

In the midst of crisis, the organization learned its insurance coverage was grossly inadequate—and it was too late to supplement or improve coverage amounts. In this case, the carrier ultimately paid the $300,000 aggregate and satisfied its obligation under the CGL policy. The organization was forced to absorb defense costs and indemnity out-of-pocket.

Before crisis hit, the organization should have secured sufficient coverage limits and considered acquiring additional supplemental and umbrella policies. When queried concerning the efforts of the organization’s insurance agent, the organization’s leader/CEO responded that the agent relationship was inherited from a predecessor; leadership did not know the identity of the agent or have contact information.

Notice to Insurance Carrier

Additionally, leaders (and, therefore, all staff members) were unfamiliar with specific state reporting requirements related to an allegation of abuse or neglect (discussed below in Reporting Requirements), as well as the “notice” requirement contained in all insurance policies.

The “notice” provision generally reads like this:

In the event the insured receives information about facts that could give rise to a claim, the insured is required under this policy to notify the insurance carrier immediately, but not later than 24 hours.

The organization received an allegation several months earlier but considered the information “hearsay”—an oral report from a parent about inappropriate touching described by their seven-year-old daughter. This communication should have triggered a communication by the organization’s representative to their insurance carrier. Failure to notify an insurance carrier in this circumstance can result in a “reservation of rights” or a denial of coverage by the carrier. Either scenario places the organization in an adversarial position with its insurance carrier. In the above situation, the carrier weighed its options and simply tendered its limits because the aggregate ($300,000) was insignificant compared to the cost of filing a Federal Court lawsuit seeking a Declaratory Judgment against the organization (seeking a court finding that the organization breached its duty to notify the carrier, which relieves the carrier of its obligations to provide indemnity or defense).

The Sexual Abuse Fire Drill can be helpful in assessing insurance availability and sufficiency. By assuming a multi-victim allegation involving a trusted staff member or volunteer, the organization may evaluate all insurance instruments for potential coverage (CGL, D&O, E&O, Umbrella, etc.), confirm limits provided, and clearly understand any limitations. The organization should include its insurance agent in this evaluation.

The organization’s leadership should clearly understand when to notify the carrier and what information to include. A timely and proper notification to a carrier is far more likely to occur when staff members have been trained to understand the risk of sexual abuse and the common behaviors of sexual abusers. Some entities receive information, but do not appreciate, until much later, that the information received clearly provided “facts that could give rise to a claim.” As a result, it is important that the organization’s staff members and volunteers have a practical understanding of the “grooming process” of the sexual abuser, and that leaders understand the specific requirements of each policy concerning notification of the carrier.

A Note on Insurance Agents

An organization’s insurance agent fills an important role in the organization’s risk management effort. The agent should have a strong understanding of the organization’s industry, coverage needs, unique risks, and methods to reduce these risks. Too often, an agent can assist an organization in the purchase of Property & Casualty coverage, but remains ill-equipped to address the risk of sexual abuse and related coverage needs for a particular organization. Part of the Fire Drill should be an evaluation of the insurance agent to satisfy the organization that the agent is familiar with the unique risks that face the organization and necessary safety system elements to reduce risk in light of legislation and licensure issues. As well, an agent should be able to assist the organization with reporting requirements to the authorities and insurance carrier, when necessary.

To equip insurance agents and risk managers in this area, attorneys at MinistrySafe and Abuse Prevention Systems have created a Risk Manager Tutorial—a three-part video series that provides an instructional overview regarding sexual abuse risks, assessment and pitfalls. (Click here to access tutorial.)

State Law Reporting Requirements

Every state in the United States has legislated reporting requirements related to child abuse and neglect. These requirements vary state by state, but all states have defined “mandatory reporters”—adults who are required by law to report suspected abuse or neglect. In some states, all adults are mandatory reporters. In others, specific professionals or individuals in child-serving positions are mandated to report abuse or neglect. Organizational management should research state reporting requirements in the areas it provides services and train personnel to understand and apply relevant state reporting requirements.

Because all states have legislation protecting “good faith reports” of abuse or neglect, it is always best for organizations providing services to children to err on the side of protecting the children they serve by reporting suspected abuse or neglect, whether mandated to do so or not.

Sexual Abuse Safety System

Many organizations are operating without an adequate system to reduce the risk of child sexual abuse. Unfortunately, many organizations serving children cannot effectively evaluate this risk because sexual abuse is a risk its leadership and management personnel do not understand.

It’s impossible to prepare for a risk that you don’t understand.

Before a “Fire Drill” has value, an effective Safety System must be in place. To assess system effectiveness, these questions should be answered:

- What Safety System is in place, and what are its specific components?

- What constitutes a “reasonable Safety System” for your program? (What is “enough?”)

- Does the system include training components for staff members and volunteers?

- Does it include an effective screening process?

- Do staff members and employees know “what to do” when an allegation is received?

Five elements of an effective Safety System are described below. A seven-part video tutorial, created by MinistrySafe and Abuse Prevention Systems attorneys, is designed to assist leadership in the creation of an effective Safety System (“How to Create a Safety System”). This video tutorial is available at no charge through MinistrySafe.com (https://www.ministrysafe.com/safety) and Abuse Prevention Systems (https://www.abusepreventionsystems.com/safety).

Elements of an Effective Sexual Abuse Safety System

An effective Safety System should be designed to reduce the risk of sexual abuse and should contain the following elements:

1. Sexual Abuse Awareness Training

Awareness Training is the foundational element of an effective Safety System. Sexual Abuse Awareness Training equips leaders, staff members and volunteers with a better understanding of the risk of sexual abuse by providing information, including:

- A portrayal of facts and common misconceptions concerning abuse and abusers

- Common abuser characteristics

- The “grooming process” (selecting and preparing a victim for abuse)

- Common grooming behaviors

- Peer-to-peer abuse

- Short and long-term impact of abuse

- Reporting abuse to supervisors and authorities

Awareness Training provides critically important information to staff members and volunteers. With an understanding of an abuser’s “grooming behaviors,” staff members are better equipped to recognize these behaviors within the context of a particular program model. For example, “grooming behavior” in a youth sports environment may appear different from “grooming behavior” at camp or in a youth ministry program. Awareness Training equips staff members and volunteers with “eyes to see” and “ears to hear” abuser characteristics and grooming behaviors.

Effective policies and procedures should be shaped around an understanding of the abuser’s grooming process and grooming behaviors. Through Awareness Training, staff members and volunteers can be trained to better understand the purpose of policies, therefore serving more effectively within policy boundaries, and recognizing problematic behaviors before an abuser has made sexual contact with a child. Because leadership, staff members and volunteers have been trained to understand grooming behaviors, all are better equipped to receive and report allegations, both internally and to appropriate authorities.

Changes in the Law. Given recent changes in state laws related to child abuse, it is widely expected that Sexual Abuse Awareness Training will be required by law in future for organizations providing services to children. The Texas Youth Camp Act, for example, requires state-approved Sexual Abuse Awareness Training for all youth camps and day camps in Texas (click here for more information). Similarly, Texas Senate Bill 1414 requires state-approved Sexual Abuse Awareness Training for all colleges and universities in Texas providing programs for minors or hosting such programs on campus. Other states are considering comparable legislation. In the near future, mandatory Sexual Abuse Awareness Training will be required in child-serving environments throughout the country. Sexual Abuse Awareness Training provided by MinistrySafe and Abuse Prevention Systems is compliant with all current and anticipated legislative and licensure requirements.

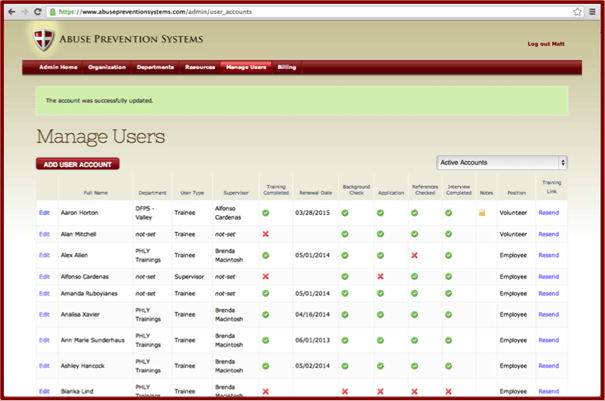

Available Online. Through MinistrySafe or Abuse Prevention Systems membership, organizations can access online systems to provide Sexual Abuse Awareness Training to staff members and volunteers, track training results and periodically renew certification. To learn more about MinistrySafe online training system, click here. To learn more about Abuse Prevention Systems online training system, click here. Click here to learn more about MinistrySafe membership. Click here to learn more about Abuse Prevention Systems membership.

Live Trainings. Sexual Abuse Awareness Training for child-serving organizations is available live throughout the United States, presented by attorneys and sexual abuse experts Gregory Love and Kimberlee Norris. When offered live, this training may be tailored to an organization’s specific circumstances, services or needs. Click here to learn more about Love and Norris, or here for our live training schedule.

2. Skillful Screening

It’s impossible to screen for a risk that you don’t understand.

Many organizations employ a screening system, but do not understand high-risk behaviors or indicators of an abuser. Such screening systems have limited effectiveness in identifying the wolf (abuser) before it enters the sheep pen. Skillful Screening is a critical component of an effective Safety System. An effective screening process provides an opportunity for gathering information about an applicant to determine whether the applicant is a high-risk candidate.

A skillful screening system utilizes forms and processes meant to illicit high-risk responses from applicants or references. Effective screening forms are available to MinistrySafe and Abuse Prevention Systems members from the Resources Library at MinistrySafe.com and AbusePreventionSystems.com.

Skillful Screening Training

“Forms are just paper” unless screeners know what to look for.

A screening system is most effective when screening and managerial staff members have received Skillful Screening Training. This training includes:

- Recognizing and identifying high-risk behaviors

- Using screening forms and processes to elicit high-risk responses

- Getting peak value from references

- Using the application and interview to evaluate applicant risk

- Understanding the uses and weaknesses of a criminal background check

- Recognizing evasive answers and “non-answers”

- Utilizing follow-up questions when receiving an evasive answer or “non-answer”

An effective screening system requires the use of tailored screening forms, designed to elicit high-risk responses, overseen by staff members trained to recognize high-risk responses and undertake the necessary follow-up.

Skillful Screening Training is available live and online, presented by attorney and sexual abuse expert Kimberlee Norris. When offered live, this training may be tailored to an organization’s specific circumstances, services or needs.

Online, Skillful Screening Training is presented in eleven segments, approximately 3.5 hours in length, and may be accessed by contacting MinistrySafe or Abuse Prevention Systems at 817.737.7233.

Skillful Screening Training builds on the foundation of Sexual Abuse Awareness Training; all trainees should have completed Sexual Abuse Awareness Training prior to viewing Skillful Screening Training, which assumes some mastery of the concepts explored in Awareness Training.

3. Appropriate Criminal Background Check

Most child-serving organizations are undertaking criminal background checks; commonly, this is the primary “screening” component utilized. Many organizations lack good information to understand the realities of the criminal justice system and limitations of a criminal background check. Consider this statistic:

Less than 10% of sexual abusers will ever encounter the criminal justice system. More recent studies indicate less than 3% of abusers will ever be prosecuted.

Given this reality, assuming a criminal background check system is working perfectly (which is unlikely), more than 90% of individuals who have sexually abused children have no past criminal record—and these individuals know it. Making a reasonable effort to access past criminal history has become a standard of care for organizations serving children, but a criminal background check should not serve as a stand-alone safety system.

Recognizing Plea-Down or Stair-Step Offenses. A criminal background check provides one piece of useful information in an effective screening process. Occasionally, screening staff members will get a “hit” on an applicant’s criminal background check. They many times fail to recognize the “high-risk” nature of the reported offense because the screener has not been trained to recognize “plea-down” or “stair-step” offenses. In criminal prosecutions related to sexual crimes, it is common for a first-time offender to be offered the opportunity to “plea to a lessor offense.” Though the abuser may have been arrested and charged with “aggravated sexual assault of a child,” his legal counsel may negotiate a plea arrangement allowing the abuser to plea guilty to a lessor (sometimes non-sexual) charge, such as simple assault. Though the behavior and arrest related to the sexual abuse of a child, the conviction and subsequent record has no reference to sexual behavior or wrongdoing. Offenses that bear investigation include: assault, indecency, voyeurism, exhibitionism, contributing to the delinquency of a minor (alcohol, tobacco or pornography), or any other charge encompassing nudity or minors.

Skillful Screening Training provides critical instruction concerning the effective use of criminal background checks, plea-down and stair-step offenses. To learn more about online Skillful Screening Training, click here.

Disqualifying Offenses. In 2010, Texas became the first state in the United States to publish a list of criminal offenses that “disqualify” an applicant from working at a youth camp or day camp. As well, the Texas Youth Camp Act includes a list of offenses which may not preclude an applicant (paid or unpaid) from working with children at camp, but require the hiring organization to undertake additional due diligence. Click here for information concerning the Texas Youth Camp Act, as amended (2010), with analysis and commentary (relevant section—page 10 of 45).

Refresh Background Checks. Many child-serving organizations undertake a criminal background check when an individual applies for a position, but never refresh the criminal background check subsequently. In our law practice, assessments reveal that many child-serving organizations have employees or volunteers serving literally decades without any subsequent refresh of an initial criminal background check. Best practice? Renew criminal background checks for all staff members and volunteers every two to three years.

Integrated Background Check System. With a newly offered service, MinistrySafe and Abuse Prevention Systems members may request and track criminal background searches utilizing the organization’s online control panel, providing a complete screening system in one easily managed location.

4. Tailored Policies and Procedures

Many child-serving organizations have “policies,” written or unwritten. When an allegation of sexual abuse is made, both defense counsel and plaintiff’s counsel will immediately request the organization’s “policies.” Sadly, many organizations learn in the midst of litigation that policies are what you DO, not what you SAY you do.

Policies should be tailored. A common error revealed in crisis relates to poor policies. In the creation of policies, many organizations don’t know “where to start,” and policies are cobbled together from multiple sources. Because “you can’t reduce a risk you don’t understand,” cobbled policies, based on limited understanding, rarely adequately address this risk. A church shouldn’t attempt to utilize policies prepared for the Boy Scouts; a little league team shouldn’t try to use policies prepared for the YMCA, and so on.

To design and implement tailored policies and procedures, leadership should first gain a better understanding of sexual abuse and sexual abusers, as well as specific risks manifest in their particular service or type of programming. Armed with this knowledge, leadership should locate a good “core policy” directly related to the organization’s program or type of service. Policies should dovetail with and be grounded upon a strong understanding of the grooming process, abuser characteristics and common grooming behaviors; this information is provided by Sexual Abuse Awareness Training, described above.

Sample policies are available to MinistrySafe and Abuse Prevention Systems members for schools, school athletics, camps, youth sports, children’s ministry, youth ministry, day care, and other child-serving endeavors. Sample policy forms are color-coded with periodic instructions for tailoring the form for specific organizational use. For a list of resources available to MinistrySafe members, click here. For a list of resources available to Abuse Prevention Systems members, click here.

Importance of Awareness Training. Policies are just PAPER without training. Excellent policies on paper do not insure effective implementation of policies! Absent effective training, staff members and volunteers will rarely embrace “change,” even in the form of well-crafted policies. Sexual Abuse Awareness Training provides the necessary information (the “why”), allowing staff members and volunteers to understand and embrace effective policies (the “what”).

5. Monitoring and Oversight

Sexual abuse of children is a large and growing issue. After an effective safety system is tailored and implemented, systems of monitoring and oversight ensure continued diligence, such that “you DO what you SAY you do.”

To this end, child-serving organizations should periodically review safety system elements, evaluate new programs for child protection issues, address any need for policy changes or updates and ensure the inclusion of safety system concerns in performance reviews and accountability. Periodic review helps ensure that child protection is not jeopardized by the departure of one or two key staff members or volunteers.

Control Panel. For MinistrySafe and Abuse Prevention System members, the online control panel provides an essential component of the Monitoring and Oversight System. The control panel allows an administrator to monitor and track training, screening and criminal background checks, and can be set up for multiple access points to ensure smooth transition when an administrative staff member or volunteer leaves the organization.

Conclusion

The purpose of a “Sexual Abuse Fire Drill” is to ensure an organization has appropriate insurance coverage and a sound safety plan—prior to a crisis. This Drill is also an important opportunity for an organization to communicate expectations to all involved and determine necessary changes or improvements. In the midst of a crisis, it is too late to prepare; the catastrophic event simply reveals whether a child-serving organization took reasonable steps to prepare for a foreseeable event—an allegation of sexual abuse.

Written by Gregory S. Love and Kimberlee Norris