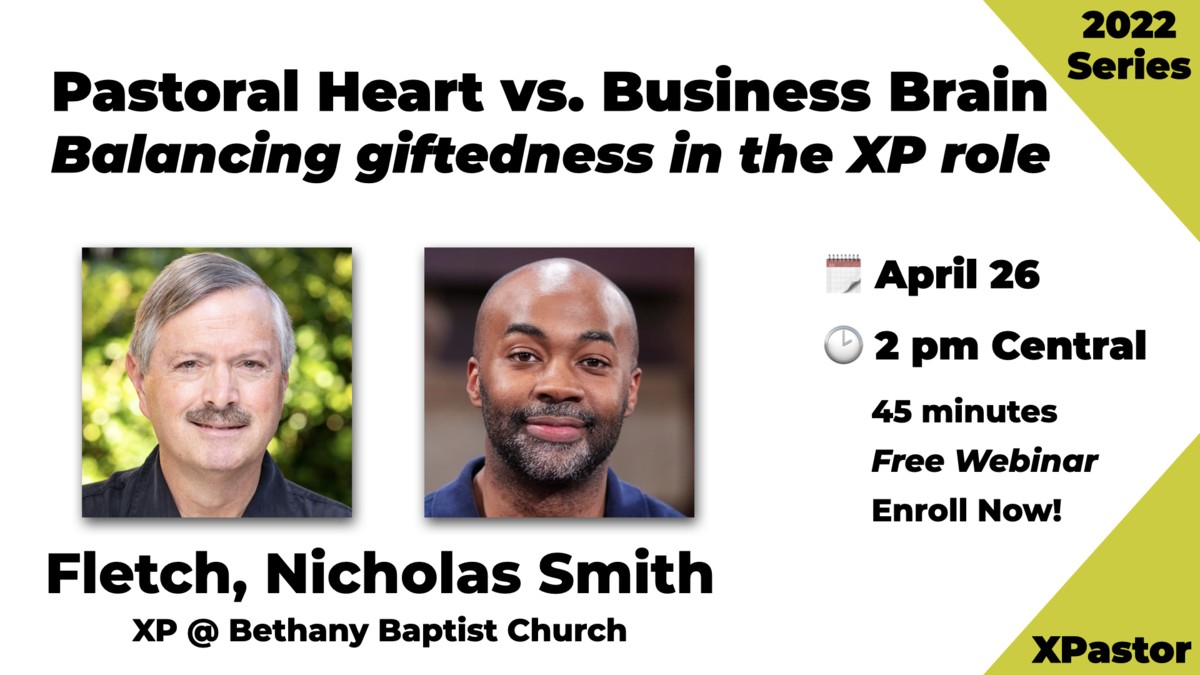

Bob Buford passed away recently. If you’re younger than about 40, it’s possible you’ve never heard of Bob Buford. But if you’re an executive pastor of any age, you owe your position to Bob Buford.

Bob Buford with his mentor, Peter Drucker, in the background

Here’s the history, as I know it. Bob Buford was born in 1939. His mother owned a local television station in the then-small town of Tyler, Texas. When he was still in his early twenties, his mother died in a hotel fire in Dallas, leaving Bob to run the family business on his own.

Bob parlayed that single station into a succession of stations that he bought and sold. Then in the 1980s, cable television began to come into its own with the founding of HBO, America’s first pay-TV network. While most of the big players competed to wire up major markets in big cities, Bob pursued a more cost-effective strategy of securing cable licenses in tiny, overlooked towns and hamlets across the South.

At the time, cable was somewhat of a second-class player in the broadcast industry, which was dominated by the major networks. Bob never struck me as second-class, so one day I asked him why he went into cable. “That’s easy,” he replied, “I wanted to get into something where even the dumb guys were making money.”

Bob was definitely no dumb guy, and he ended up making quite a bit of money! By the time he reached 40, he had reached most of his entrepreneurial goals. So he began to pray and reflect on what really mattered to him, and how he should invest the rest of his life.

His mentor was Peter Drucker. If you’re not familiar with Drucker, the second thing you need to do after reading this post is to go to Amazon and download Drucker & Me: What a Texas Entrepreneur Learned from the Father of Modern Management. Bob kept only two books on his desk. One was his Bible. The other was Drucker’s classic, Management: Tasks, Responsibilities, Practices.

Twice a year, Bob would fly out to the West Coast to spend a couple of days with Peter. He returned with legal pads of scribbled notes capturing Drucker’s insights into the practice of business. Bob implemented those practices, and the rest, as they say, is history.

Now here’s where Bob’s story begins to intersect with yours. Peter identified three major sectors in our culture: business, government, and nonprofits (or the social sector). Peter predicted that the greatest innovations in the latter half of the 20th century and the first half of the 21st century would mostly happen in the social sector. So he advised Bob to focus his efforts there.

Peter further pointed out that the largest player by far in the social sector is churches. So he further advised Bob to “find the islands of health and strength” among churches and assist them in accomplishing their mission. At the time, those islands turned out to be a small but growing number of large, entrepreneurial, innovative churches that came to be called megachurches (originally defined as churches of 1,000 or more people, later as 2,000+).

With that customer in mind, Bob formed Leadership Network (LN) and began inviting pastors and senior leaders of megachurches to gather for discussion forums at Glen Eyrie in Colorado Springs, with LN picking up the tab. Originally, the agenda of those meetings was to have no agenda. That was a direct application of Bob’s preferred model of learning: “Just put all the smart people in a room and they’ll figure out what to talk about.”

Among the earliest issues those leaders surfaced was the problem of managing these new, large, complicated organizations called megachurches. Most of the founders were entrepreneurial and visionary, but by no means gifted at administration. Now they were leading thousands of attendees and hundreds of volunteers, overseeing large and even massive campuses, and managing multi-million-dollar budgets. Someone had to translate all of that vision and adrenaline into strategy and action.

It didn’t take long for the forums to figure out who that someone should be: the executive pastor. A relative handful of people had de facto been playing that role within larger churches in the 1960s and ’70s—most notably within some of the larger Southern Baptist churches, as well as at flagship congregations like Lake Avenue Congregational Church in Pasadena, California (Jerry Johnson); First Church of the Nazarene, also in Pasadena (Dick Pritchard); Skyline Church in La Mesa, California (Dan Reiland); First Evangelical Free Church at Fullerton, California (Paul Sailhamer); Crystal Cathedral in Garden Grove, California (Glen DeMaster); and Grace Chapel in Lexington, Massachusetts (Warren Schuh).

But it was the rapid expansion of megachurches—greatly facilitated by Bob and LN—that ended up formalizing, legitimizing, and truly authorizing executive pastors to function in an executive role, with real responsibility for results (akin to P&L responsibility in the corporate world).

In short, Bob introduced the practice of organizational management to the church—which is to say he introduced Peter Drucker to the church (along with other thought leaders of the day, like Peter Senge, Ken Blanchard, Jim Collins, etc.) Some people since then have criticized churches for adopting practices from the business world (perhaps betraying a perilous commitment to a sacred-secular dichotomy). They fear that an emphasis on things like goals and accountability and analytics will eclipse trust in God and reliance on His power, and ultimately undermine the church’s mission.

Without question, that’s a potential danger. But with his uncanny knack for putting his finger on fundamentals, Drucker countered that “the reason churches need management is not to make them more business-like, but to make them more church-like.” Churches absolutely have a mission to carry out. And that mission is not about administration and management. But, if a church is not administered and managed well, it cannot carry out its mission well.

That’s where the executive pastor comes in. The executive pastor exists to ensure that his/her congregation is able to execute its mission with excellence because the church is run with excellence.

Earlier I said that downloading Bob’s book about his fascinating relationship with Peter Drucker is the second thing you need to do after reading this post. By all means do that! But first, why not take a moment to thank God for the life and work of Bob Buford?

I don’t think anybody questions that the rise of the megachurch was a key inflection point in the history of American Christianity. Ironically, Bob was not a megachurch pastor, and in fact was never even a member of a megachurch. But his fingerprints are all over the megachurch movement. And the creation of the executive pastor is one of the most valuable contributions he leaves behind.